Stop going for 2 down 8

What if the analytics people are flat out wrong?

I always forget how boring football gets in October. Man, did Sunday’s football feel less controversial yesterday than in previous weeks. The 6:30 AM game was a total clunker between the Broncos and Jets, featuring negative ten passing yards by the losing team. I watched my favorite team overcome incompetent officiating and two of the worst offensive pass interference calls I’ve ever seen. The Chiefs beat the Lions handily in primetime. The product suffers in October, but the NFL prints money nonetheless.

I guess if nothing stands out, you can just beat your hobby horse as a columnist. You can talk about how October games tend to be boring. You can talk about your favorite home team. Or you can watch for people doing a dumb strategy over and over and write about it.

On this last point, Sunday did not disappoint. I caught the end of a snoozer game where the Bengals did the go-for-two-down-eight (G42D8). For having been signed on Wednesday, forty-year-old quarterback Joe Flacco was surprisingly elite, lifting a team without hopes to a single score against what was supposed to be a dominant Packers defense. Of course, the Bengals still lost.

Remarkably, the Jaguars also did the G42D8 move on Sunday. They also lost! Despite never seeming to work, this analytics-inspired move of futility appears to be the default action for those desperately trying to win a game. In 2025, we’re now 0 for 4 when teams try the two-point conversion upon cutting the lead to 8.

But this got me curious: has this G42D8 play ever worked? I knew it had worked twice. The most famous article about the G42D8 strategy by Seth Walder was republished after the 2023 Packers beat the Saints using the maneuver. I also recall watching the Titans, who had started the remarkably incompetent Will Levis, pull out a G42D8 move in their fourth-quarter walk over the Miami Dolphins on Monday Night Football.

I was so curious that I signed up for a subscription to stathead.com so I could be a real analytics guy.1 Cracking my knuckles, I started doing some database queries: Since the NFL adopted the two-point conversion in 1994, the G42D8 strategy has worked… exactly twice.

Yes, the only two times the G42D8 move has led to a win were the two games I just described.

You might counter that teams trying to make up 14-point deficits don’t win that frequently. That’s fair! We need a denominator to know how successful the play is. I wasn’t sure where to start counting. Where did this G42D8 meme come from in the first place? Walder’s article referred to an audaciously arrogant piece—typical of the hubris of the founder—on two-point conversion analytics on fivethirtyeight dot com. There, Benjamin Morris wrote:

“Despite the revolution taking place in basketball, despite Theo Epstein ending the two greatest curses in sports, despite AlphaGo going 60-0 against top human players, despite all evidence to the contrary, football stubbornly clings to the notion that experience always trumps analysis.”

Woo boy. Now we’re cooking. Morris argues that since the NFL moved the extra point attempt from the two-yard line back to the fifteen-yard line in 2015, the lower success probability of the kick makes G42D8 a far better strategy.

Alright, so since 2015, when the spreadsheet boys had convinced themselves that they were so much smarter than football coaches, how many times have teams gone for two when down 8 in the fourth quarter?

Thirty-six.

That’s right, in ten and a half seasons, the G42D8 strategy has led to a win two times out of thirty-six attempts.

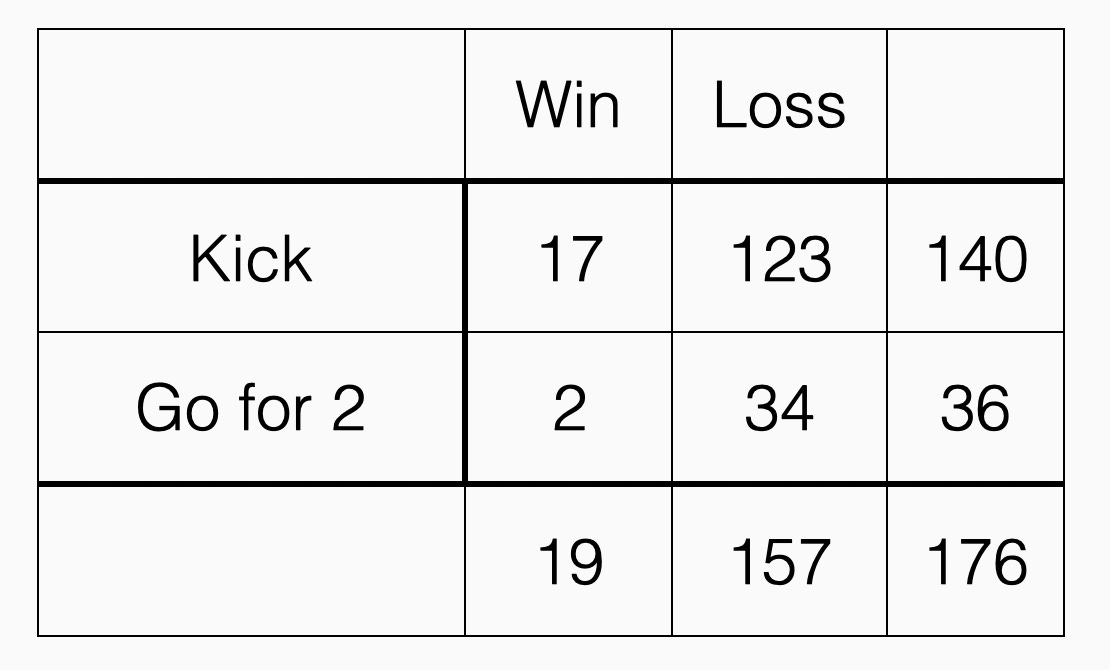

Of course, there’s another statistic we need to look at. The other option available to a football coach down 8 in the fourth quarter is kicking an extra point. Since 2015, teams down eight have attempted an extra point 140 times. Of those 140 games, teams have won 17 times. If you prefer percentages, the G42D8 strategy has resulted in a win 6% of the time. The meathead strategy, derided as cowardly and conservative by the spreadsheet jockeys, has won 12% of the time. Something is wrong with your models, analysts.

Here’s a contingency table for my statistician readers:

This brings me to another one of my statistical hobbyhorses. If you can count successful events on your fingers, you can stop looking at percentages and ad hoc identification strategies and just look at the individual cases. There have been only two instances in the past ten seasons where this strategy has led to a win! What happened in those games?

In the Packers game that inspired Seth Walder’s ESPN victory lap, the Packers nearly lost. Saints kicker, Blake Grupe, barely misses a walk-off 46-yard field goal. Grupe was 8 for 10 from that range in 2023, and his kick was just wide right. You might say in this case that the Packers were metaphorically hitting on 18. Sure, their decision played out right, but only because an event with an 80% chance of success didn’t pan out.

The Titans-Dolphins game was equally fluky. The Titans had mostly dominated, and both of the starting star wide receivers on the Dolphins got hurt. But sloppy turnovers, two due to incompetent rookie quarterback Will Levis, had given the Dolphins a few short fields to go up by two touchdowns.

With five minutes left in the fourth quarter, the Titans pulled it together and effortlessly marched down the field. The Dolphins’ defense made Will Levis look like Tom Brady. He threw the ball 9 times for 80 yards on that drive. On the final two touchdown drives of the game, Levis had almost a perfect passer rating, only spoiled because they let Derrick Henry run in the last score.

The two-point conversion in this game was a statement of aggression. Since the Titans had been able to pass at will, why not add one more pass to really hammer home the point? Coach Mike Vrabel wanted to break the Dolphins’ spirit, showing them that their defense couldn’t even stop Will Levis in the red zone. Could it be that football is psychological?

Certainly yes in myriad ways. The Athletic reported that Vrabel was on the hot seat during that game. The owner had grown increasingly frustrated with Vrabel, partly due to his wanton disregard for analytics. And apparently the Titans’ internal analytics staff openly questioned the two-point decision!2

It may be the analytics proponents who are paralyzed by the outcome bias, not the rest of us. Their dumb calculation has worked twice, and one of those times was after ignoring the advice of the team statisticians. Their constant, obnoxious assertion that their strategy is better than the status quo is not remotely reflected in reality. Remarkably, their armchair bullying has won out, probably because owners love efficiency calculations. More teams are trying their losing strategy than ever before.

I know I’m beating a dead horse at this point. Everything I said in my casual blog from twenty months ago was right. Unlike baseball, football is not well modeled as a simple Markov process. There is not enough data to make clean statistical inferences. Probabilistic models based on counts don’t capture outcomes. Yes, NFL teams might have bought into the analytics hype of the 21st century, but it has borne little fruit. And yet, despite all evidence to the contrary, people still think football is as easy to analyze as Go.

ETA: I mistakenly double-counted four games in the original draft of this post where two-point attempts were repeated because of penalty. That is, there were only 36 attempts of the G42D8 strategy, not 40. Thanks to football analytics guru Buttadeus for pointing this out.

It took me a minute to get a handle on how to query the database, so you didn’t get this column on Monday. But whatever, this blog has no deadlines.

For non-football fans, Levis was benched a week later after a poor showing against the Texans. Vrabel was fired at the end of the season.

Hello, sports analytics apologist here. I saw your article referenced in a Defector article so thought I'd chime in.

First, as others have mentioned, I think this kind of observational analysis is super important to pressure-test sports analytics maxims like G42D8. Often times, these analytics ideas do not really incorporate any intangible and/or psychological factors that may be present in sports (momentum, clutch, chemistry, etc). I do think you are on to something but did have a few comments:

(Semantics point): G42D8 is not really based on modeling and empirical evidence, but rather math with strict assumptions. If you assume your OT win rate is 50% AND that you have enough time for exactly only one more offensive possession in regulation, you really only need your 2P conversion success rate to be ~35% in order for it to be worth it on paper. I read your previous article, so yes I know that the chances of winning the game are extremely low no matter what. G42D8 is not a silver bullet, but rather a last-ditch effort to improve win probability as much as possible. The reason I point this out is that the assumptions do some heavy lifting in the "G42" argument.

How many of the 17 wins in your "Kick" dataset did the comeback team have multiple regulation possessions after the first TD? G42D8 assumes that the comeback team only has time for one more possession in regulation. If comeback team scores the TD+XP, gets ball back and scores another TD+XP, and gets ball back again and kicks a FG, then I would argue that there was too much time on the clock for this truly to be a G42D8 scenario. The only outcome in which "Kick" would be better is if they make both XPs to send the game to OT, and then they win in OT (while in the counterfactual, they miss both 2P conversions so game does not reach OT).

Perhaps the argument is that analytics people are over-applying G42D8, and in cases where the comeback team has more bites at the apple. I have definitely seen Seth use it where there was clearly too much time in the 4th. I agree that there should be more nuance about when in the fourth quarter it actually applies. Or maybe it's that you cannot reliably predict how many more possessions you have left in a game, which makes G42D8 moot.

Another key assumption is that the probability of getting the ball back without surrendering points is independent of the decision to go for 2 or kick. In reality, missing a 2-point try might affect defensive morale or aggressiveness, just as converting it could give a psychological boost. That’s an interesting empirical angle to explore. Similarly, it would be interesting to analyze whether the comeback team is truly 50% in OT. Could be they are more likely to win because of something like momentum. Could be they are less likely to win because they are probably the inferior team.

Sample sizes are small, but they are always small in football so I'm not going to dismiss your analysis for that reason. It does mean though, as you mention, that we kind of have to look at this anecdotally, and understand the contexts of each game, which is why I asked about the context of the 17 wins earlier. At the end of the day, I just hope more teams continue to go for 2 so we can get more data!

Is it possible to look at cases only where the trailing team scored the two regulation TDs required to fully test the theory? I.e., strip out times where they went for two/kicked the XP but then never scored again anyway.