Reformist Reinforcement Learning

What if we just begin and end with policy gradient?

The final week of the semester coincides with the annual AI Winter megaconference, and so I’ll lean into posting about AI this week. And given the spiritual syzygy, I’m going to focus on a fascinating intersection between AI methods and AI culture: Reinforcement learning.

Reinforcement learning is a weird subfield of AI that has plagued me since I got to Berkeley. I have written about it countless times. I have an old, pre-substack blog series about it. I wrote a whole survey about it. I wrote more recent substack posts about it. I helped found a conference about it!

But even after all of that, I still have a tough time explaining what reinforcement learning is. It’s incredibly hard to pin down. That’s because it’s more of a culture than a body of technical results. If you read the main book by the Turing Award winners in the field, it’s supposedly the foundation of all automated decision-making, mimicking natural intelligence in people and animals.1 If you look at what the heuristics do in practice, they’re “use a mixture between your current strategy and some noise to try a bunch of random stuff, then tune your strategy’s parameters in hopes of mimicking the subset of stuff that looked promising.” This is not how people or animals do things, no matter what stories RL people spin about narrow, debunked behaviorist psychology.

The challenge of explaining reinforcement learning is the quasireligion that arises when the name is spoken. Those really enamored with reinforcement learning speak in a very complex liturgy that’s hard to parse unless you’ve committed yourself to the discipline. The name carries an air of unpredictable magic that allows you to solve unsolvable problems. People say “we’re using reinforcement learning” and, without any other results, that somehow gets you a billion-dollar company. I mean, sure, why not?

But I don’t want to spend a week trying to explain what reinforcement learning is again. This gives it more of an air of mystery and power than it deserves. Explaining TD-learning only ensures more prestigious awards and seed rounds for the RL crew. And the dirty secret is most of these methods don’t work that well!

In a class, I think the only way around this morass is to take a radically minimalist view of reinforcement learning and say that it’s just policy gradient methods. Policy gradient covers all of the applications of RL in language models and 95% of applications of RL outside language models. For the remaining 5%, you can take a pilgrimage to frozen Alberta.

I call this narrow view reformist reinforcement learning. In reformist reinforcement learning, we don’t need all that much fancy math. I don’t need to tell you what “on policy” vs “off policy” means (if you care, not much!). I don’t need to introduce insane dynamic programming notation and advantage functions or costs to go. I don’t have to remember the difference between policy iteration and value iteration. You don’t even have to learn what a Markov Decision Process is. If you don’t know what any of these terms mean, consider yourself lucky! You can throw all of this jargon in the trash. There’s just one idea, it’s straightforward, it’s very universal, and sometimes it works. You start here, and then you can add on the bells and whistles if you really want to.

I can explain reformist RL in a paragraph. I’ll need a couple of equations, but if you understand stochastic gradient descent, you’ll understand this too.2 Indeed, Reformist RL is just a specialized application of the stochastic gradient method.

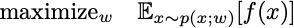

Reformist RL considers optimization of probability distributions. The goal is to maximize the expected value of some random variable. In an equation, we want to solve the optimization problem

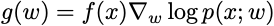

The w are the parameters that define the probability distribution. They can be the actual individual probabilities or parameters of a generative model discussed in the last lecture. It turns out that if we sample x from p(x;w), then

is always an unbiased estimator of the gradient of the objective function. This means that if you can sample from p(x; w) for any setting of the weights, you can run stochastic gradient ascent on the objective you care about. That’s it. For historical reasons, stochastic gradient with this gradient estimator is called policy gradient. You choose a distribution parameterized so you can sample from it. You draw samples from your current distribution. You tune the weights to increase the probability where the samples found promising values.

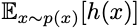

This method of throwing spaghetti at the wall is incredibly general. It gives you a heuristic for every optimization problem! Let’s say you want to maximize the function h(x). This is equivalent to maximizing

with respect to all probability distributions, p(x). The optimal distribution has all of its mass on the x that maximizes h. If instead of optimizing over all probability distributions, you can restrict your attention to distributions that you can sample from and whose gradients are nice. When you do this, you get an approximation algorithm for free. Is the approximation good? No one knows! I can pose undecidable problems this way, and I have no idea what happens when you try to solve those with policy gradient methods. But now every optimization problem is an RL problem. RL lets you try stuff. And if you have infinite compute resources, why not do this? It’s easier than thinking, right? That’s the Bitter Lesson.

I can never shake the audacious ambition of this quote from Sutton and Barto:

“A good way to understand reinforcement learning is to consider some of the examples and possible applications that have guided its development.

“A master chess player makes a move. The choice is informed both by planning--anticipating possible replies and counterreplies--and by immediate, intuitive judgments of the desirability of particular positions and moves.

“An adaptive controller adjusts parameters of a petroleum refinery’s operation in real time. The controller optimizes the yield/cost/quality trade-off on the basis of specified marginal costs without sticking strictly to the set points originally suggested by engineers.

“A gazelle calf struggles to its feet minutes after being born. Half an hour later it is running at 20 miles per hour.

“A mobile robot decides whether it should enter a new room in search of more trash to collect or start trying to find its way back to its battery recharging station. It makes its decision based on how quickly and easily it has been able to find the recharger in the past.

“Phil prepares his breakfast. Closely examined, even this apparently mundane activity reveals a complex web of conditional behavior and interlocking goal-subgoal relationships: walking to the cupboard, opening it, selecting a cereal box, then reaching for, grasping, and retrieving the box. Other complex, tuned, interactive sequences of behavior are required to obtain a bowl, spoon, and milk jug. Each step involves a series of eye movements to obtain information and to guide reaching and locomotion. Rapid judgments are continually made about how to carry the objects or whether it is better to ferry some of them to the dining table before obtaining others. Each step is guided by goals, such as grasping a spoon or getting to the refrigerator, and is in service of other goals, such as having the spoon to eat with once the cereal is prepared and ultimately obtaining nourishment.”

The methods in the book, of course, solve none of these problems.

For everyone else, I think I can write a blog post that explains this without equations. Let me know if you’re interested.

Yes do please

Oh boy. This one is hitting close to home...

I totally get the appeal for a "reformist" view. I'm also sympathetic to the idea that all these RL methods basically do "the same" thing, and that this "thing" is a rather simple random search style [for those who remember, we discussed this here: https://open.substack.com/pub/argmin/p/why-is-reinforcement-learning-so?utm_campaign=comment-list-share-cta&utm_medium=web&comments=true&commentId=18055037]

Having said all that, I'm also not sure that the "pure PG" view totally saves you here.

To explain why, I'm going to take the liberty and write my version of your promised blogpost:

So here's RL without equations. In order to learn-by-doing, you iterate the following two steps:

1. Try to estimate how good you're currently doing

2. Adjust what you're currently doing so that you are [slightly] better the next time around.

This is basically what Sutton and Barto termed "Generalized Policy Iteration" in their book. The 2 steps doesn't have to be as distinct, can be partial/parallel, etc.

Now,

- In a "vanilla" REINFORCE, you do step 1 in the most straightforward / naive way possible, by just collecting a handful of samples and relying on Monte-Carlo, and you do step 2 in a "sophisticated" way of taking gradients of your policy directly.

- In TD, you do step 1 in a slightly more sophisticated way (which is possible because you bring in more assumptions about the structure of the task), using approximated dynamic programming. you do step 2, otoh, in a kind-of stupid way by acting greedily wrt your current estimate from step 1.

But **crucially**, you still need both steps either way you're going about it. The reason you need (1) is that there's no teacher (which, for me, *is* the fundamental defining property of "what is RL").

Shameless plug: I've written a short paper about this earlier this year, from the perspective of RL in CogSci/Nuero (I know, I know -- we aren't allowed to refer to these fields on this blog...).

It turns out that quite a few people advocated for a "reformist" view there as well, promising that if we start and end with PG we will resolve a lot of conceptual issues with our models (of animal/human learning and behavior). I disagree with this claim, and I outlined the main argument of the short paper above here (there are a few more points discussed in the full text).

I will very much appreciate your thoughts, if you want to read it (short, i promise), it's available here: https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.04822