Inference and The Psychoanalytic Interview

Meehl's Philosophical Psychology, Lecture 11.

This post digs into Lecture 11 of Paul Meehl’s course “Philosophical Psychology.” The video for Lecture 11 is here. Here’s the full table of contents of my blogging through the class.

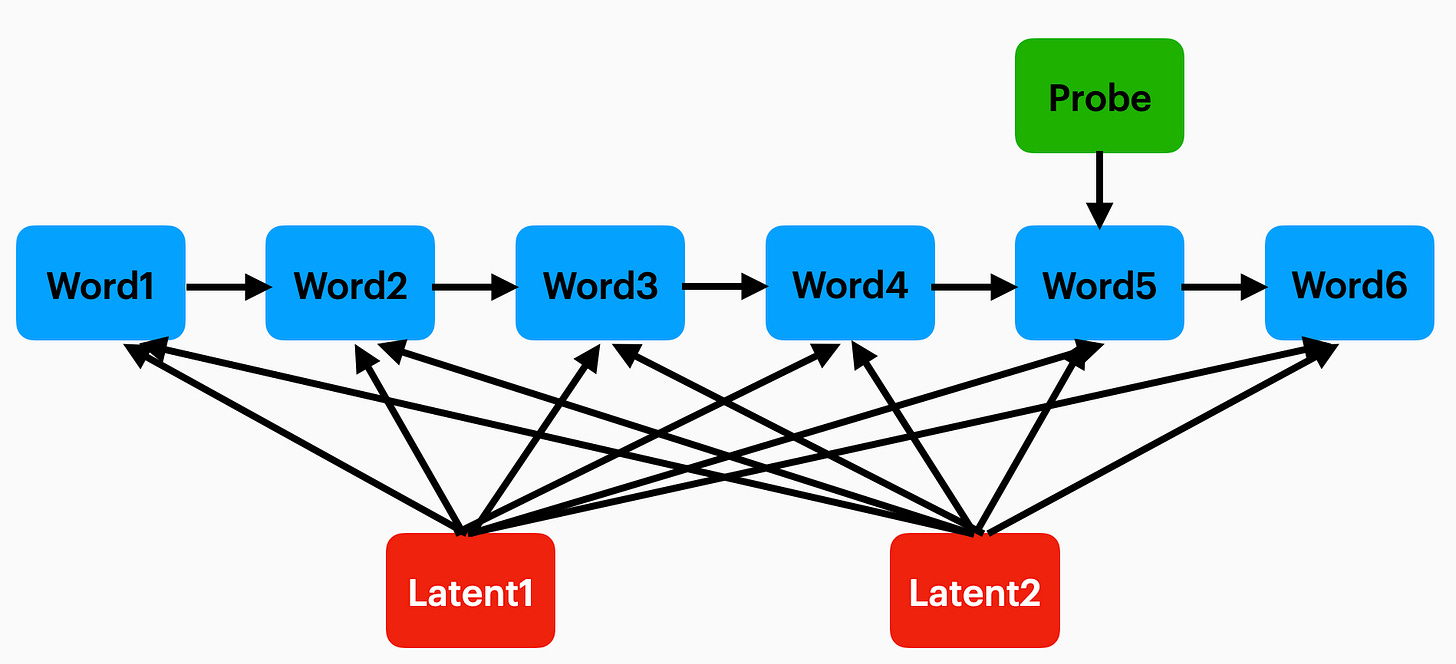

The International Conference on Machine Learning is this week. So let me set today’s stage with an AI problem. Suppose I have a sequence of symbols that I model as generated by some semi-parametric process. My goal is to infer the latent state of that process. I can choose a set of actions to probe the system and see how the sequence changes. What is the optimal algorithm for inferring the latent state?

I’m sure there’s some poster in Vienna1 right now that has this model in the abstract. They probably use LLMs or something. Whatever the case, this model is also Paul Meehl’s formulation of the psychoanalytic interview as a problem in inference.

The sequence in psychoanalysis is the words uttered by the patient. The latents are the repressed memories or emotions impinging on the observed utterances. The patient is talking about what they intend to talk about, but the therapist seeks to infer the latent sequence that is impacting unintentional parts of the monologue. There are pauses, blanks, and rate of speech that are all possibly caused by the latent stream. The therapist can occasionally interject to see if they can steer the conversation toward confirming their suspicions. Can the therapist infer the latents? The abstract model of psychoanalysis is a complex game of Bayesian inference with a clinical chatbot.

Meehl gives several examples of how such Bayesian-ish inferences work in psychoanalysis through his own case studies, and I can’t do them justice in a blog. It’s worth watching the lecture to fully immerse yourself in the complexity and nuance.

Sometimes, the examples are obvious. A woman drops her wedding ring in the toilet. She calls her husband by the wrong name. She has a headache after date night. While you could come up with lots of behavioral explanations for each of these events (acute clumsiness, temporary disassociation, food poisoning), a considerably simpler model is that one latent issue (insecurity about her marriage) explains the disconnected events.

Sometimes, especially when it comes to dream interpretation, the inferences are far more complex and entangled. Meehl describes linking a patient’s dream about a dying asian man to the cover of Time magazine featuring Burmese prime minister U Nu, which he linked to the patient being astounded and incensed by the sorts of deductions Meehl would make in therapy (“you knew!”), which he linked to the patient's general inferiority complexes for not finishing college.

The examples of Lecture 11 illustrate the craft of psychoanalysis. It needs a lot of training and skill to perform well. How can we evaluate if it works? Does it actually work to ameliorate mental health problems? Here is the main philosophy of science problem. Meehl was disappointed to say that, almost 100 years after Freud, no one knew the answer. Another four decades later, and I don’t think we have much more clarification.

Mental health and therapy are certainly less stigmatized than they were in the 1980s. Such conditions and treatments are considered “real” and “scientific” by a large medical community. But psychodynamics remains part of the “less scientific” corner of mental health therapies, losing favor to more “testable” interventions like cognitive behavioral therapy and an army of pharmaceuticals. But do those therapies actually work better? Why do we think so?

You can’t deny that psychoanalysis is empirical. The protocols are based in observation and intervention. The case studies provide plenty of clear evidence. You could videotape sessions if you needed absolute concrete “evidence.” But the evidence is never quantitative. Even though therapists make inferences, they can’t convert psychoanalytic sessions into numbers. Probability 1, as we’ve discussed now, is barely quantitative. It might not be quantitative at all.

You can’t dismiss psychoanalysis on the basis of its inherent subjectivity. All Bayesian inference is subjective! Subjectivity is the foundation of the entire Bayesian statistics program. Is a sophisticated mathematical model of a patient’s utterances (say, a multi-plate latent Dirichlet model) less subjective than proposing they are impinged by an Oedipus complex? Of course not. Even the most radical millenarian rationalists commit to the inherent subjectivity of inference.

Perhaps you can say that adherents of psychoanalysis cherry pick the positive examples. Psychodynamic therapy can take years to work, and it’s hard to tabulate its success rates. Perhaps its effects are heterogeneous, where it only works for some people and not others. The entire enterprise could be resting on 100 years of motivated reasoning. But there are enough revelatory examples in talk therapy, examples where people’s anxieties vanish in a single session, to think that something is going on.

There’s such a sharp contrast between Lectures 10 and 11. In Lecture 10 we discussed problems with clear-cut outcomes and simple interventions. For these, we could just tabulate statistics and predict what to do. Everything reduced to simple probability calculations. Find the smallest reference classes with stable frequencies and use these frequencies as degrees of confidence about the future. We could tell a clean quantitative story and even outperform clinical judgment.

Psychoanalysis is the entire other end of the spectrum. It requires a highly trained analyst, multiple interactions over potentially long time horizons, open-ended decision-making with unclear and flexible rules, high subjectivity, and little quantification. You can do RCTs of psychodynamic therapy. Unsurprisingly, there aren’t that many of them, and the assembled evidence is inconclusive.

In our age of randomized trial-o-mania, treatments gain popularity solely because they can more easily survive randomized trialing. But, because I cannot say it enough times, randomized trials provide an impoverished view of causality. Simply measured interventions are rarer than we’d like them to be. Even if we know the effect of a single drug on some disease, we rarely have an evidence base for two drugs. What about actual clinical practice? There are so many complex protocols that aren’t easily RCTed. Coaching, tutoring, artistry, craftsmanship. We don’t need RCTs to know these skills work. RCTs and other quantitative experiments have their time and place, but it’s worth noting that we can find things that work without such rigid statistical dogma.

The frustrating thing for many scientists is there will always be a fine line between math and metaphor. But mathematical metaphors untethered from quantification are undervalued. Being able to manipulate metaphors with mathematical poetry is a valuable means of understanding method. Mathematical metaphors can tell us what matters. They can tell us what doesn’t matter. They can simplify how we train clinicians. They can provide good heuristics for what we try next. They can help us understand what works.

Oh, the Freudian irony here…

Some notes

- You may want to read Freud's early work, from Studies in Hysteria to his metapsychology papers like "The Unconscious" where he shows in detail his thought processes, coming up with hypotheses and refuting them. The classic critique of Freud that you see in Popper is a gross misrepresentation, even a critic of psychoanalysis like Grunbaum thinks it's bad.

You might be interested in the French school of psychoanalysis, which honestly makes much more sense in the context of French philosophy of science, which was rationalist compared to the Anglophone-analytic tradition. There's a very powerful and interesting epistemological tradition from Bachelard, Canguilhem, Cavaillés, Koyré—which spawned a psychoanalytically informed epistemological tradition in the Cahiers pour l'Analyse, and Lacan wrote a few key texts on science, like the brilliant "Science and Truth". Jean-Claude Milner has a brilliant book on Lacan and science, "A Search for Clarity" that I recommend, Lacan is much better imo than the characterization you see in Sokal and others. Lacan's analysis anyway is that psychoanalysis is not a science, but has the emergence of science as a condition—I recommend Milner's account.

Also, Freud wrote up one of the first diagrams of neural networks in his unpublished Project for a Scientific Psychology. There's a book, Biology of Freedom, by a Lacanian and a neuroscientist, on this topic. Also Liu's awesome book Freudian Robot on the intersection between psychoanalysis and the history of AI

>All Bayesian inference is subjective! Subjectivity is the foundation of the entire Bayesian statistics program.

Not sure exactly what you mean by this, but its a bit triggering :-). If by subjective you mean something like 'dealing in degrees of belief' and/or 'depending on external prior information' than I would much rather be the explicitly "subjective" Bayesian than be implicitly credulous and even outright wrong the way many routine applications of frequentist statistics are.