Frame by Frame

Optimization vs systems-level synthesis

Kevin Baker’s essay on AI for science highlights the tension between the optimization and systems views of scientific inquiry. Is science an optimization problem where we can pose discovery as an outcome to maximize given what we already know? Or is discovery a complex process of interaction between scientists and the manuscripts they share?

It’s a bit of both. There are certainly focused problems in science that can be aided by a maximization engine. Alexandre Passos lays out a strong case in the comments of my post from Monday.

“At least the science I am a little familiar with involves throwing a bunch of reasonable sounding alternatives from literature on a relevant problem, often mixing them with each other a bit, to build an intuition of what works well where.

“And when you think about this, this sounds a lot like the basic requirements for reform RL to work: you have a bunch of reasonable strategies you can initialize a model to do, applying a reasonable strategy to an in-domain problem has a nonzero success percentage, and mixing and matching pieces of reasonable strategies has a single digit percentage chance of improving something.”

Alexandre’s description here is consistent with Baker’s view that mathematical optimization is a technology. It can collect data based on our current understanding of the world and provide a new materialized view, like a telescope. We still have to convince our friends that what we see in the readout of the optimized science machine is worth seeing. The assembly of a scientific record doesn’t happen through rational Bayesian confirmation.

However, I’m sure that you can make progress leveraging optimization in science, provided you have framed your scientific problem correctly. If you

have a reasonable model of the world represented by the scientific literature

can mathematically characterize what you need for a publishable unit

can try a lot of different options and evaluate their worthiness

then you can optimize.

Many people conclude this maximizing program applies to any problem where we need to act and learn from the world. Everything is optimization, right? If I can optimize science, I can optimize ethics:

“Imagine any popular ethical thought experiment. It involves some actor in a situation with some well-defined entities. You’re walking alongside a river, there’s a drowning child, and you are wearing a fancy suit. The ethical decision about whether to save the child hinges on how fancy your suit is, your estimate of the physiognomy of the child (he looks like he might be >95th percentile criminality :-/ ) and your monetary discount rate divided by your timeline for AI X-risk…”

This quote comes from another provocative Substack exposition by a person named Kevin. In this case, it’s Kevin Munger, who writes that computational thought experiment ethics like this betray a constrained belief system.

[T]he message is that the world consists of entities like “suits” and “rivers,” that a few sentences are sufficient to define a human’s experience of the world, and that those humans have an essentially unlimited amount of time to perform those calculations.

We designed computers to be automated optimizers from the get-go, and they are thus limited in the sort of problems they can solve. Since computers have gotten faster faster than we collectively have gotten smarter, we convinced ourselves that the optimization lens is the right way to think about interaction with reality.1 Our data-scientific tools designed to run on computers and make decisions end up being optimization engines, whether they are machine learning, optimal control, stochastic programming, or reinforcement learning. All measured quantities become optimization targets within bureaucracies through Merton’s goal displacement. Our computational, scientific, and social systems all swarm to optimize. It’s not surprising that people popularly convince themselves that life is just an optimization problem, no matter the paradoxes, contradictions, or repugnant conclusions.

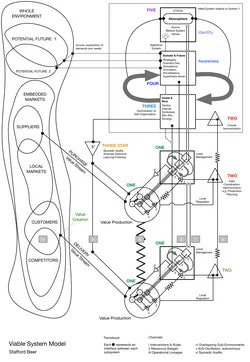

Munger’s dip into utilitarian thought experiments comes in a longer piece about the antimimetic nature of systems-level thinking. Everyone understands that there is more to existence and action than a framed collection of substances and their relative optimality. Reality is probably better described by complex interactions between systems with cascades of feedback. But anyone who tries to explain things this way starts sounding like a crazy person. Either they start telling you about chaos and fractals, or they start writing down impenetrable ramblings about mathematical control theory, or they draw complex systems diagrams like this one from Munger’s post.

Munger argues that process remains resistant to computation, education, and discussion. Why is it so hard to understand feedback systems? Why must all actions be posed as the optimal solution of optimization problems? Why is process an antimeme? I’ve scatteredly blogged about this topic before, but I’ve never found satisfying answers. But I’m going to dip in again this week on the blog. I’m foolishly going to teach a whole course on this topic next semester. Maybe I’ll finally unearth systems-level ideas that can go viral. Tell me next Spring if you think I’ve lost my mind.

I confess the intractability of "systems" never seemed especially mysterious to me. Maybe this is an advantage of being a bit stupid. I was never smart enough that I should expect to understand things, so things not being understandable never seemed especially mysterious.

From this idiot's view: the obvious thing missing in ethics, and also in most of social science, is that last bit about "being able to try a lot of different options and evaluate their worthiness". But this isn't anything intrinsically mysterious about the problems, it's just that the problems are Too Big to practically experiment and iterate on.

If you could grow hundreds of human economies in a controlled laboratory environment over the course of a few weeks, we might understand economics as well as we do fruit flies--which is to say, highly imperfectly, but better than we do actual economics. If you could do the same thing with ethical principles--maybe engineer some virtue-knock-out spiritual leaders or something--then maybe we could find out with some certainty which ethical principles are most conducive to human thriving.

But since we are inside the system, living at the timescale of the system, we can only ever iterate on and optimize small subproblems. Try to do anything else, and you are necessarily generalizing far beyond your tiny slice of space-time data. Of course it doesn't work!

I agree that in the biological and biomedical sciences things are messier, but maybe not only because we lack good models. Even if we had perfect knowledge of the underlying biochemistry/biophysics at the molecular level, there might be fundamental limits of the systems approach itself. Anderson's "More is Different" paper from 1972 comes to mind. While reductionism (breaking things down to fundamental laws) is powerful, the reverse is not trivial. Knowing the parts and their interactions doesn't automatically yield understanding of the whole, because at each hierarchical level of organization, new laws, concepts, and phenomena emerge that are irreducible in practice.

YET, at the same time, I find it really interesting that in biology evolution-driven optimality principles are deeply reconciled with systems-level thinking, emerging bottom-up from complex, feedback-rich processes involving constraints, historical contingency, and rugged fitness landscapes rather than imposed top-down.

Some of us think that this makes biology a domain where the two perspectives complement each other: systems views illuminate the dynamics shaping optimization, while optimality provides strong predictive power under intense selection.