Random Search for Random Search

Digging into specific applications of policy gradient

This is a live blog of Lecture 22 of the 2025 edition of my graduate machine learning class “Patterns, Predictions, and Actions.” A Table of Contents is here.

In yesterday’s post, I wrote about policy gradient:

“If you can sample from p(x; w) for any setting of the weights, you can run stochastic gradient ascent on the objective you care about. That’s it.”

But I need to be fair, “it” is quite a lot. Today’s lecture expands on this simple idea, showing that it lets you build heuristic optimization solvers for almost anything. To explain this, today’s post will be far more technical than yesterday’s. Tomorrow’s post will be far less technical.

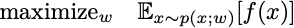

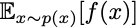

The sorts of problems we want to solve are maximizing an expected value with respect to some family of probability distributions:

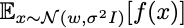

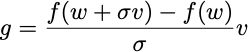

The w are the parameters that define the probability distribution, and these are what we’ll search for. The main idea driving all policy gradient methods is the following observation: If x is a sample from p(x;w), then

is an unbiased estimate of the gradient of the objective function. The term b(w) is called a baseline. It is a design parameter in the policy gradient method. If you are clever, you can often devise a baseline that reduces the variance of the gradient estimator, improving the performance of the algorithm.

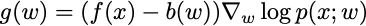

The proof that the policy gradient is unbiased is a few lines of algebraic manipulation, which I’ll include here for completeness, as it is the intellectual core of Reformist RL.

The first equality plugs in the definition of expected value. The second equality uses the fact that integration and differentiation commute. The third equality multiplies and divides by a positive number inside the integral. The fourth equality is applying the chain rule in reverse. The fifth equality again uses the definition of expected value. The final equality follows because the expected value of grad log p is zero. QED.

Now that we have that out of the way, we can start applying this gradient estimator to derive algorithms. And it’s sort of surprising how many we can derive from this one gradient estimator.

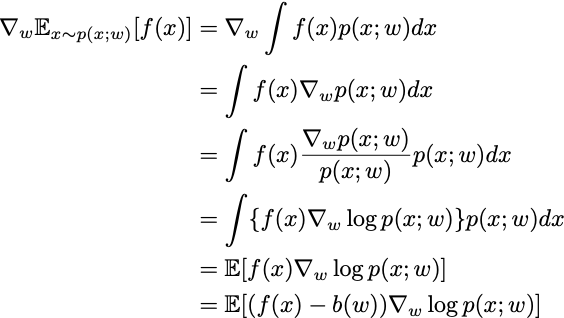

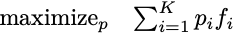

The first example to look at is applying policy gradient to the simple optimization problem over a vector of probabilities.

The parameters in this formulation are just the K individual probabilities themselves. These parameters must be nonnegative and sum to 1. Policy gradient here works by sampling an index i from the multinomial distribution defined by p, and applying the resulting gradient estimator

where ei is a standard basis vector. After a gradient step along this direction, the resulting vector p is assuredly not a probability distribution. You have to project it back to the probability simplex somehow. One valid method is to compute the closest probability distribution in Euclidean space to your iterate. Another way to ensure your iterates remain valid probabilities is to use stochastic mirror descent rather than stochastic gradient descent. Stochastic mirror descent applied to the policy gradient is called EXP3. It is the core algorithm for solving the nonstochastic multiarmed bandit problem. That is, applying policy gradient to online convex optimization recovers a theoretically optimal algorithm.

For most problems where we want to apply policy gradient, it’s hard to write down the problem as sampling from a simple monomial distribution. Consider the simple case where the “x” in question is a real-valued vector. As I mentioned yesterday, maximizing

over all probability distributions is equivalent to maximizing f(x) itself. Hence, if you could sample from p(x), you could apply policy gradient to any optimization problem. The optimal distribution would have all of its mass on the maximizing x.

But there are only a few distributions p(x;w) for which we know how to reliably draw samples. Let’s look at one specific case. What happens if we restrict our attention to approximate delta functions, defined by normal distributions with small variance?

For small enough variances, maximizing this function with respect to w is the same as maximizing f. What is the stochastic gradient?

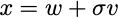

Well, the first thing you need to do is sample an x. This is easy. You sample a vector v from a Gaussian distribution with mean zero and identity variance and set

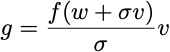

The gradient estimator is then

But now I can apply a baseline, and I’ll get a much more interesting form:

This gradient estimate is a finite-difference approximation of the directional derivative of f at w in the direction v. Policy gradient, in this case, is equivalent to choosing a random direction and following a finite-difference approximation to the gradient in that direction. This algorithm isn’t the worst thing in the world, and Nesterov and Spokoiny proved it converges to a global optimum when f is concave. Rastrigin proposed such a heuristic in 1963 and called it random search. For some reason, other people think of this as a genetic algorithm. It’s a fine heuristic.

It’s not a great heuristic. This algorithm only works well if the objective function is differentiable. However, if you could compute its gradient, you would have a dramatically faster algorithm. Gradient descent is always faster than random search. It’s very rare that you have a differentiable function but without means to (automatically) computing its derivative.

The intrepid are not deterred by impossibility results. Nothing is stopping you from delving deeper into this development of heuristics. You could apply it directly to the optimization of Markov Decision Processes and get the classic Policy Gradient algorithms that are usually taught in reinforcement learning classes. You could apply it to language models and get out “RLVR” and “GRPO” and “GFYPO” and the other heuristics people use to train language models to solve math problems (lol, reasoning). I’ll blog about this more later this week.

And yet, policy gradient does force you into a corner with its requirements. You can only optimize over probability distributions from which you can sample. You need to be able to compute the derivative of p with respect to its weights. You need to be able to compute f. You need insights to make sure the number of steps doesn’t exceed the number of atoms in the universe. The fact that you need heuristics for baselines is annoying, too. You never know what a good baseline heuristic looks like; you just have to play around to find something that works. A baseline that works for one problem probably won’t work for another. No matter what RL people tell you, the stars have to align for policy gradient to work. It is not like scipy.minimize.

My beef with general-purpose optimization heuristics is that a single tool is never all you need. There is no free lunch in optimization. I don’t think you should solve ordinary least-squares problems with policy gradient. You’ll be waiting a long time. I also don’t think that you should solve SAT problems with policy gradient. In my experience, if you can get policy gradient to work, there’s another simple heuristic nearby that will give you a few orders of magnitude of speedup. In the age of scaling, efficiency is underrated.

I don't know what if anything you can do but your equations are not readable in dark mode