Evil Andrew Huberman’s Fitness Program Can’t Fail

About two years after starting CrossFit, I became obsessed with programming. I was an optimization researcher! I lived and breathed mathematical programming. What was this “fitness programming” all about?

CrossFit is arranged around hour-long classes. After warming up, in the first half of the class, you work on “strength” and in the second half you work on “conditioning.” A typical strength portion might be “do 3 sets of deadlift, 3 reps each set, with 80% of your maximum possible deadlift weight on the bar.” A conditioning portion would be “For 11 minutes, do as many rounds as possible of 5 burpees, 5 pull-ups, and 7 handstand pushups.” I know, I know, CrossFit is ridiculous.

From the start, I noticed patterns in what we were doing. The strength portions had a rhythm to them. We might squat every Monday. The weight would get a little heavier every week. We might break up the repetitive cycles after a few weeks, moving from back squats on Mondays to front squats on Fridays. We seemed to stick with one particular pattern for 6 to 8 weeks. There was clearly some logic to it, but what was the logic?

Enter the internet! I found out that my friend Laurent Lessard was obsessed with strength training, and he told me that he had figured out some ways to program for himself by consulting internet forums. I was intrigued.

As you are likely aware, there is no shortage of people telling you what you should do Youtube, Instagram, Reddit. Every fitness influencer has some key piece of advice that’s going to take you to that next level. (My personal favorite is Joel Seedman.) Being a science person, I checked out the “science-based” corners of fitness influencer land. Oh boy. This was a mess.

Other than a few nerds out there, no one who ends up on a science-based influencer page really wants to understand The Science. Most people are looking to grow their glutes, not to understand the Krebs Cycle. With a few rare exceptions, the “science-based” label is abused by influencers to claim false authority. This false appeal to authority is generally true of scientists, but I found sports science particularly bad. I bought several “science-based” fitness books, and they didn’t have references. Wut?

Was there any cohesive sense to any of this? The answer is yes, and the high-level answer is not that mysterious or confusing. There is one core idea that drives the entire enterprise.

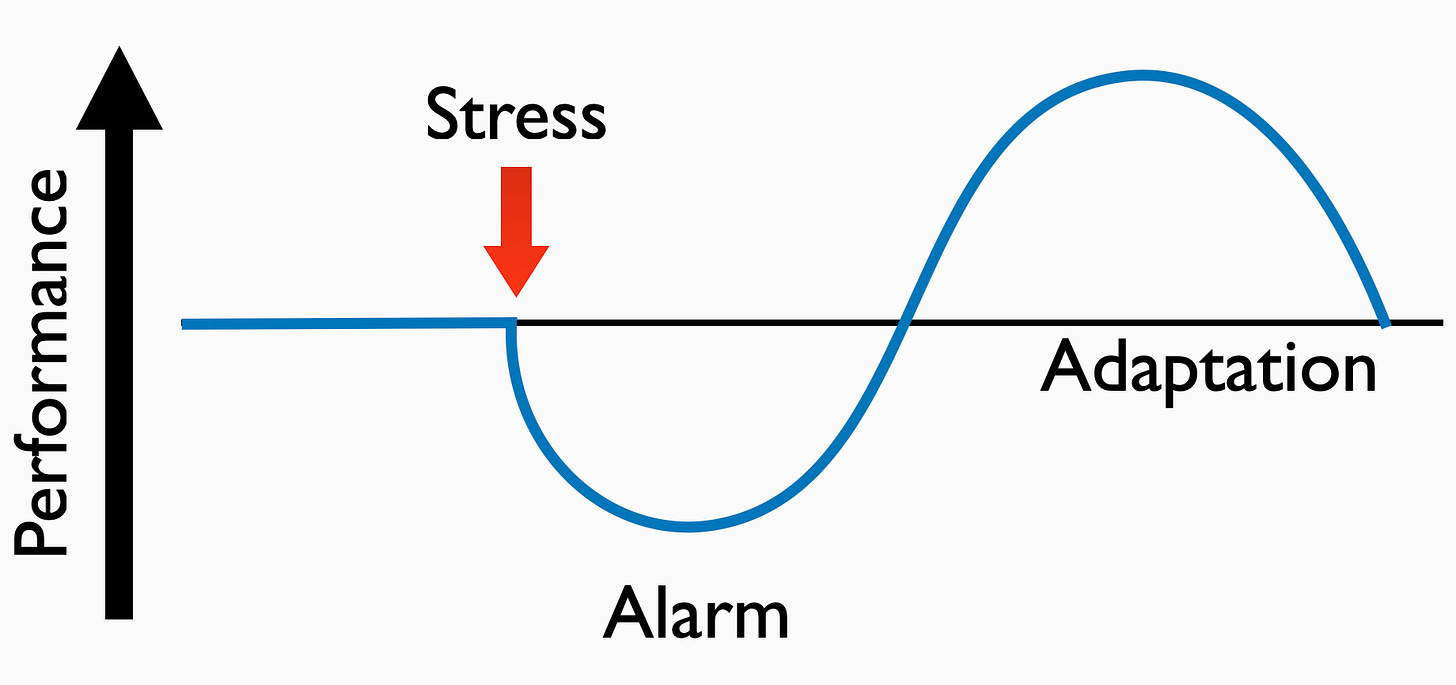

If you do something novel, your body does two things: it gets fatigued and it overcompensates to avoid excessive fatigue in case you are stupid enough to do it again. Eventually, that overcompensation recedes and you return to your original blissful baseline. But If you introduce the same stimulus early enough, your body overcompensates again. But if you keep overcompensating, you adapt so that the initial stimulus now feels like nothing, and you can handle a much larger stimulus. The idea is to progressively overload your body, inducing a chain of adaptations that increases performance.

This seems reasonable! It’s a good story! But is it true?

Training programs built on the principle of progressive overload undeniably work. It’s what almost all strength coaches use with their athletes in the weight room. More importantly, it’s what all strength athletes use to get stronger. In powerlifting, where the only goal is to get as heavy a squat, bench press, and deadlift as you can, everyone’s training is based on progressive overload.

Over the next few blogs, I will describe the basics of progressive overload and how this might shape a training program. There are so many questions to answer. Where did this idea come from? What do the resulting training programs look like? What does the “science” look like? What do the models look like? Does this mean there is an “optimal” way to program? I don’t have answers I’m particularly satisfied with, but my partial explanations have implications for much more than just fitness and sports.

It would be interesting to see what wins "science based" fitness (most of which is small sample size nonsense) has over bro science. My impression was "soreness doesn't matter" and "prioritize going close to failure" both fall in this category