Dynamic treatment as personalized medicine

A thought experiment

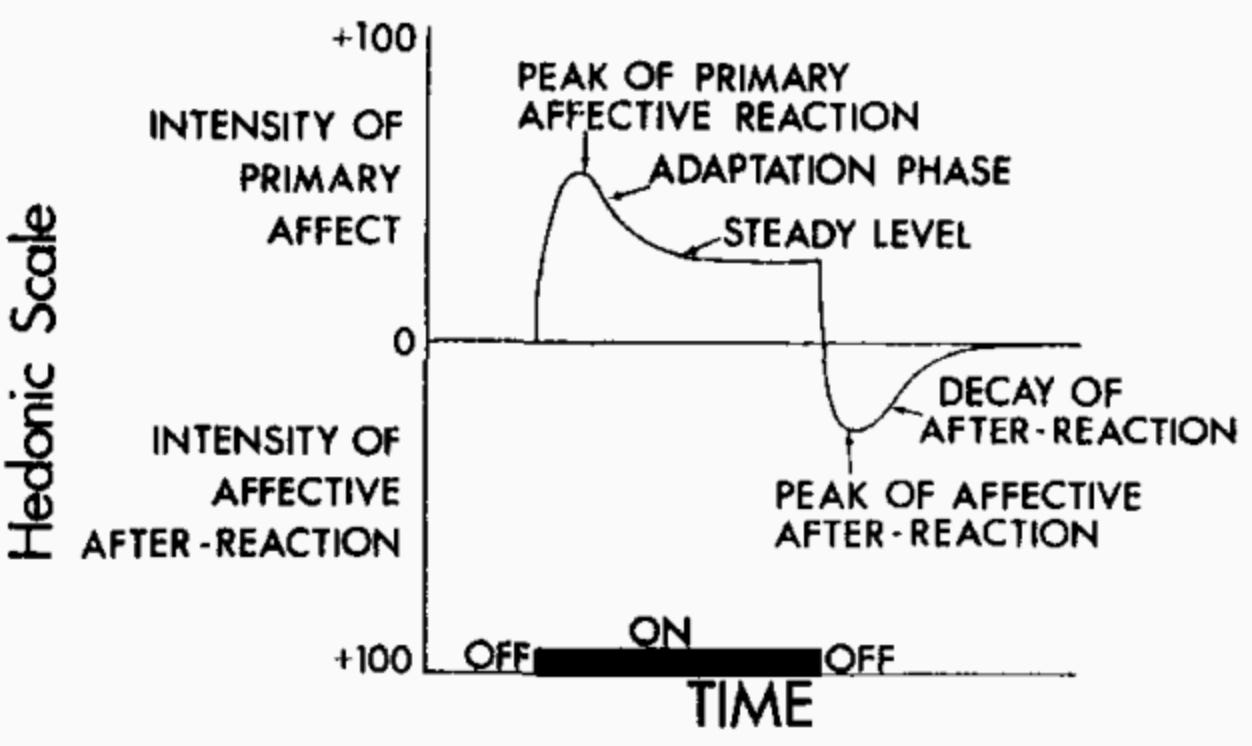

Let me get out over my skis today and think out loud about controlled adaptation outside the exercise world. In the 1970s, psychologist Richard Solomon proposed a model for addiction, aversion, and other mental processes of motivation. In his model, a positive emotional state that is brought on by some stimulus is “opposed” by a negative state that overcompensates to reduce the positive feeling. In a 1974 paper, Solomon and Corbit plot what the step response of this model would look like.

Hmm. This looks familiar. A few blogs ago, I showed this plot of Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome,

It looks like the Opponent Process is the negative of a GAS model. Is this a fair assessment? Let me quote Solomon and Corbit:

“The primary A process for a given hedonic state is aroused by its adequate stimulus. We then imagine a single opponent loop generating the secondary B process and having an hedonic sign opposite to that of the state aroused by the input. The loop generating the B process is activated whenever any input evokes a sufficient hedonic consequence. The B process is sluggish, so it has a relatively long latency, recruits slowly, and dies out slowly.”

In psychology, “hedonic” means an adaptation that increases upon a stimulus and then decays. Hedonic adaptations are most commonly modeled by first-order dynamical systems. If I were to turn this block quote into a mathematical model, I would precisely end up with a system that is a “negative” fitness fatigue model.

Paula Gradu came to me with this observation after I had been ranting in group meeting about exercise models. She wanted to know what we could do with the observation that Opponent Processes are negative Fitness-Fatigue models. What would it mean to progressively… underload (?) an Opponent Process Model? Could this be applied to helping people using addictive substances?

Here’s a thought experiment of an application that Paula came up with. Let’s imagine a person is taking a medication and would like to stop. For example, a person would like to stop using pain medication after surgery but doesn’t want to experience too much pain as they reduce their dose.

The standard recommendations for going off medications are just “take less.” The most common protocol is linear tapering. If you are taking 20mg a day this week, then take 15mg next week, 10mg the week after that, and 5mg the week after that. Then stop taking the medication. These narrowly targeted tapers assume that everyone responds similarly to dose reduction. But just like with fitness training, a single withdrawal plan shouldn’t work for everyone. People with different states of dependence will have to reduce their dosages differently. You have to meet a person where they are. What would it look like to personalize these demedication protocols?

The Opponent Process model suggests a path. In progressive overload models of exercise, a person should increase their efforts based on how much they can handle in a training session. In Opponent Process models, the “optimal” dosage is the minimum dose that will work for a person today. If the goal is to gradually reduce the dosage to zero, the model says that an individual does not need to plan out their dosing schedule: taking the minimum effective dose each day will end up with a smaller dose over time. This tapering scheme adapts to what a person can handle but still gets the dosage to zero.

Here’s a toy sketch of what this might look like. Suppose a person can rank their well being on a scale from 0 to 10 where 10 is great and 0 is the worst (I realize that self-assessment like this is itself a major challenge but go with me for a second). Let’s say they also know they never want to go below a “3” on this scale. Then a way to guess the minimum effective dose is to taper proportionally to how well they felt yesterday versus how well they are willing to feel today. For the control theory readers, this is a proposing an integral control law on dosage based on a person’s self-assessment:

hedonic margin = yesterday’s well being - minimum well being

today’s dose = yesterday’s dose - K * hedonic margin

This demedication plan is relatively simple and inherently personalized. It uses a person’s daily self-assessment to manage their dosage.

So far this is just a thought experiment. But I don’t think this proposed protocol is too outlandish. Of course, whether or not this works for demedication would need to be very carefully tested. And the logistics of such tests are certainly a challenge. Self-assessment needs to be carefully taught, dosages would need to be appropriately quantized. But a few compelling case studies could be the first step toward reimagining what personalized medicine might be.