Deciding not to decide

A last word on diet and a segue to naturalistic decision making

My diet planning experiences are a case study of naturalistic decision making. As with all case studies, it’s unclear which parts are generalizable. Not only am I a very analytical person who loves to make spreadsheets, but I spent half of my life thinking about optimization and decision making. I love to cook and enjoy inventing recipes with constrained ingredients like I’m on a 90s episode of Iron Chef. I’m way off in the tails of whatever nerd bell curve we might draw here.

But on the other hand, if an optimization “expert” has a hard time optimizing, that should tell us something, right? I know the ins and outs of the minimum-cost diet problem and have even solved some simple cases by hand using tableaus (shout out to Olvi Mangasarian, who adamantly argued for keeping tableaus in our undergrad optimization class at Wisconsin). But when it came time for me to plan my own diet, I just futzed around with an app on my phone. I found some foods that seemed appropriate and messed around with portions a bit until I hit the ballpark I was after.

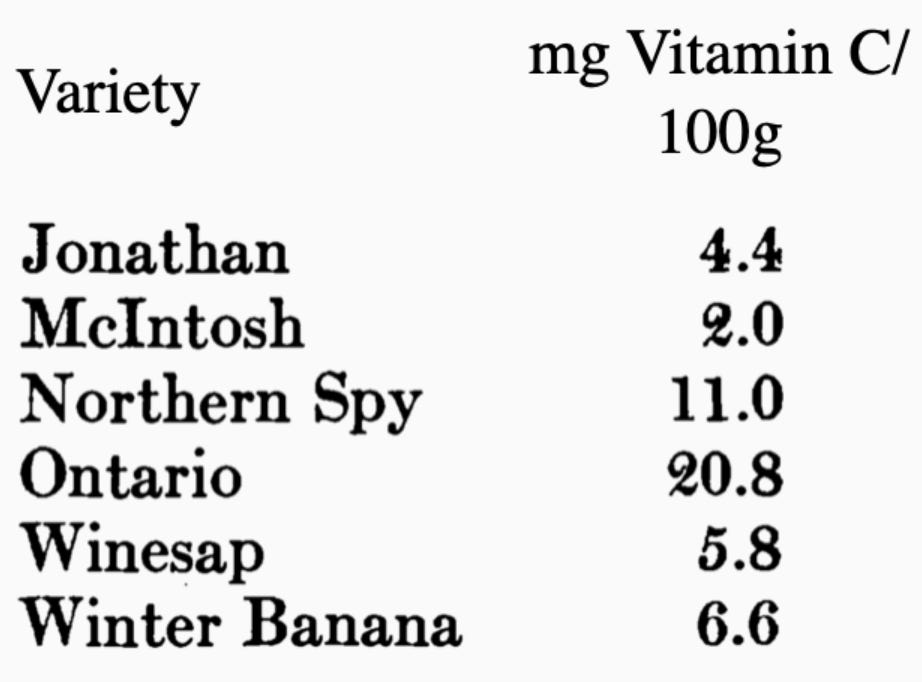

But was this app interaction actually solving the problem I cared about? I picked on Stigler’s right wing politics, but he made plenty of good points about why the diet problem is ill posed. First, the nutrient content of food varies a lot. Stigler has a great table in his paper listing the amount of Vitamin C in different varieties of apples.

There is probably similar variability in the fat/protein ratios of chickens from different farms.

Second, USDA labels are allowed to be wrong by 20%. Our estimates of how much we are consuming are necessarily imprecise.

And third, our nutritional needs are imprecise. Even for calorie intake, I found huge ranges in the online calculators, each based on wildly varying estimates of energy expenditure. I think I’m supposed to eat somewhere between 1500 and 2500. 1000 calories is quite a range! That’s a double double and fries at the In-N-Out. Or it’s 6 pounds of carrots. And if we can’t nail calories, what about the other nutrients? How much protein do we need? How Vitamin D do we need? We’re always grasping at straws here.

I bring this up to say that a diet problem isn’t even a “satisficing” problem in the sense of Herbert Simon. Satisficing means finding the first option that works. It’s different than optimizing because you are not looking for any best option, nor do you necessarily need to compare options. You can evaluate options individually and take the first one that meets your needs. But as I’ve described, if I am unsure what my needs are, and if the information about what I’m consuming is very uncertain, how do I even know I have “satisficed?”

I swear, at some point, I’m going to stop asking questions and start answering them.

In future blogs, I’ll write more about the naturalistic decision making inspired by Simon. People do not make decisions by solving complex optimization problems. Few things are easily posed as optimization problems anyway. A lot of research shows that experts use pattern recognition to make decisions. But the sort of pattern recognition used in human decision making couldn’t be farther away from how we build machines to recognize patterns. I’m interested in understanding why these are so far apart and why it’s so hard to automate human decision making. Are all attempts to automate decision making doomed to end up being blurry jpegs of conventional wisdom?

As a preview of what I have planned moving forward, the semester starts next week, and I’ll start blogging about my class. But my class is on pattern recognition and decision making (for the philistines, machine learning and artificial intelligence). I will blog about my lectures on Tuesdays and Thursdays and try to unpack some thoughts about how naturalistic pattern recognition and decision making on the other days. That should be a fun contrast, and maybe it will lead me to answers of some of these questions I’m asking.

okay but what does a winter banana apple taste like???

Deciding not to decide? You're going full Sartre on us here.